|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

About Jill McGown - Biography - Favourite Sites - Literary Links - Georgia |

Biography

"If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it." J D Salinger: The Catcher in the Rye Do you really want to hear about it? I suppose you do, or you wouldn't be here. So, all right, here goes. I was born on the 9th of August 1947 in Campbeltown, Argyll, Scotland. Campbeltown is on the Mull of Kintyre, made famous by Paul McCartney and Wings, and I knew the piper who plays the solo on the record, so there! The McCartneys moved to Campbeltown after I'd left, so I can't claim to know the great man himself. There's a link to a Campbeltown website on My Favourite Sites, if you want to see it for yourself.

In those days Campbeltown was principally a fishing town which got a lot of summer visitors. We went to Rothesay on the Isle of Bute for our summer holidays, and I expect some people from Rothesay came to Campbeltown; it was a bit like Mark Twain'sthing about people taking in one another's washing. We sailed on the turbine steamer Duchess of Hamilton, or the paddle steamer Waverley, up Kilbrannan Sound, calling at Lochranza on Arran, Ardrossan in the Firth of Clyde, and other romantic places on the way. Passengers on the Duchess of Hamilton were allowed to go down to the engine room, which I remember as being very clean and shiny and not at all like you'd imagine. Rothesay was much more sophisticated than Campbeltown; it had the Entertainers, for a start, a sort-of end-of-the-pier show that starred people like Jimmy Logan and Andy Stewart. If you don't know who they are, you are probably under fifty, and possibly not Scottish. But even more sophisticated than that - Rothesay had neon ads. Well…it had one. It was for Typhoo tea, and I could have watched it for hours. The teapot lifted up in mid-air and poured tea into a cup…it was like magic.

Campbeltown had its own delights for small children, but they were of the healthy, outdoor type - burns and hills and crab-infested rock pools, that sort of thing. I am, and always have been, an urban creature; I have a friend who says that if I go to the bottom of the garden, I think I've been on safari. This is entirely true, and was just as true then as now. My idea of fun was going to the pictures, or trundling about the courtyard of the block of flats in which we lived on a hired tricycle. And while I liked picnics on the glorious beach at Machrihanish and paddling and splashing about in the sea, I could have done without the chore of having to get out of an uncomfortable, wet, sandy bathing costume before I could get dry and put my proper clothes back on.

Machrihanish is five miles from Campbeltown, on the other side of the Kintyre peninsula, and was reached by bus; as a child, I would wait expectantly and then squeal with delight when I saw the sea. The fact that I had boarded the bus on the quayside at Campbeltown was beside the point - the Machrihanish sea was different. It was the Atlantic, blue and sparkling with white-tipped waves; the water in Campbeltown Loch was dark grey-green and so sheltered as to be almost still. But what I liked best about Machrihanish was going to my aunt's big house overlooking the ocean and picking out tunes on her piano while avoiding her psychotic cat. My father was a fisherman - he and his brother owned a fishing boat called the Felicia, and one of my earliest memories is of eating delicious prawns the size of chipolata sausages out of a jar stuffed full of them. They were fishing for herring, and the prawns weren't worth anything; times have changed. My mother was a secretary, and she had come to Campbeltown from Glasgow, so we went there from time to time to visit her brother and sister. Glasgow had the twin attractions of the subway (which is what the Scots and Americans call an underground railway), and trams. I loved both, and could never make up my mind which way I wanted to go anywhere. Trams made a wonderful clanking sound, and both ends were the front; when they reached the terminus, the conductor would go along the length of the tram, smacking all the seats so that they faced the other way for when it left again. Subway trains were noisy and frightening; I would hang on to my mother's hand, and watch for the light in the tunnel. When the one-eyed monster appeared and I could hear the rumble getting louder and louder, it scared me to death, and I loved it. Campbeltown didn't have any sort of railway, and nor, come to that, has Corby, not for people, anyway. Corby is the only constituency in Britain without a railway station, and, I'm told, the largest town in Europe without one. Somehow, Corby's like that; it's always been what the Scots call a stepbairn, and never seems to have what its brothers and sisters take for granted. We moved to Corby when the herring fishing was at an all-time low, and my father had to find work elsewhere. The Lloyds Ironworks had been built on the doorstep of what had been the tiny village of Corby in Northamptonshire, and in time the ironworks became Stewarts and Lloyds, who turned it into the biggest integrated iron and steelworks in Europe. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Corby had 820 inhabitants. At the end of it, it had 53,000. And in the middle of that century Stewarts and Lloyds was recruiting workers from anywhere it could, but mostly from Scotland. Thus Corby, in the heart of England, has Celtic and Rangers supporters' clubs, an annual Highland Gathering, shops that routinely sell oatcakes, potato scones and Scotch pancakes, and an accent which has undeniable Scottish overtones, regardless of the forebears of the speaker, who might be Londoners or Lithuanians. If you want to know more about Corby, you'll find a link to it, too. My early schooling was a little fragmented - Campbeltown had one infants school (called, by everyone, 'the wee Grammar'), and from there children went to one of the primary schools. After I had attended my primary school for two years, some of us were relocated to another one, so when I moved to Corby at the age of ten, I was on my fourth school in five years. Lifelong friendships are not formed that way, but you do acquire useful social skills.

Oddly enough, I was forced to take more to do with nature in Corby, which was devoid of anything for children to do except Saturday morning pictures. I and two friends (another girl and a boy) would play in the woods that are everywhere in Corby - sometimes the deciduous Thoroughsale Woods, where we climbed trees, and looked for acorns and conkers, sometimes the pine wood, where it was so silent you could hear twigs crackle beneath your feet, and we collected pine cones, talked, and played invented games. Children nowadays aren't encouraged to play out of doors without adult supervision, which is understandable, but a little sad. No harm ever befell us while we played - in fact, I had a happy childhood all round, and I'm thinking of suing someone over it. What use would I be on a chat-show?

From junior school, I went to Corby Grammar School, where I was taught Latin byColin Dexter who went on to write the Morse books, though I didn't know that when I wrote my first book. Our writing careers have taken exactly the same course, so I live in hope that they will continue to do so! I left Corby Grammar as soon as I could, because I didn't like it, and went to what was then Kettering Technical College, emerging two years later with shorthand and typing RSA certificates and three O-levels. I wasn't what you'd call a dedicated student. I went to work first for Corby Development Corporation, and then, a couple of years later, as a secretary in a solicitors' office. Five years after that I found myself, like fifteen thousand other people, working in what had become, with nationalisation, the British Steel Corporation. I worked there for almost ten years, during which time a voluntary redundancy programme was set up, and it became my job to collate the paperwork and counsel those who had taken voluntary redundancy as to their benefits and options. But when the steelmaking side was closed down, the voluntary scheme became compulsory and my job itself, along with thousands of others, was made redundant.

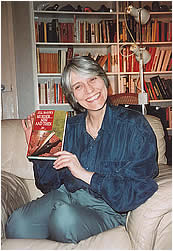

So there I was,with my redundancy pay, and a choice. I could look for another job in a town that at that time had twenty-five per cent unemployment, or I could take the opportunity to write a novel. As you'll have gathered - since I still live, not just in Corby, but in the same house that we moved to when I was ten - I am not adventurous. But this adventure had been thrust upon me, and I chose to write the novel, and forgo the regular salary. That was twenty-one years ago. It's been touch and go at times, but I've made a living of sorts by my novels ever since.

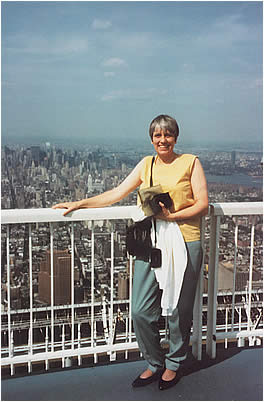

I might fill in some of those twenty-one years at a future date, but writing for a living instead doing a real job was the single biggest change in my life – there isn’t that much to write about. My parents are no longer with us, and as you can see from the updated family photograph, we now live in colour rather than black and white and the next generation has joined us in the shape of my niece Katy, but that’s about it! Twenty-one years has now turned into twenty-five. It’s 2006, and last year my niece Katy produced Georgia Wilkinson, who is the most cheerful baby in the world. If you want proof, click 'Georgia photos' on the left. She was three months old when the mother and baby photo was taken.

She celebrated her first birthday on 21 May, and Katy is already

threatening us with a five-girl photo session to go with the one

of the four of us. It might have been four years ago, but I haven’t

forgotten how painful it is to produce these poses. You have to

sit on one another’s feet and endure elbows in your ribs,

smiling gamely all the while. It isn’t all beer and skittles

having your photograph taken, you know! But to Georgia life simply

is all beer and skittles, and long may that prove true for her. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| View the full sitemap |

|